The Vieille Montagne in Germany

The Vieille Montagne in Germany

an article by Daniel Sobanski

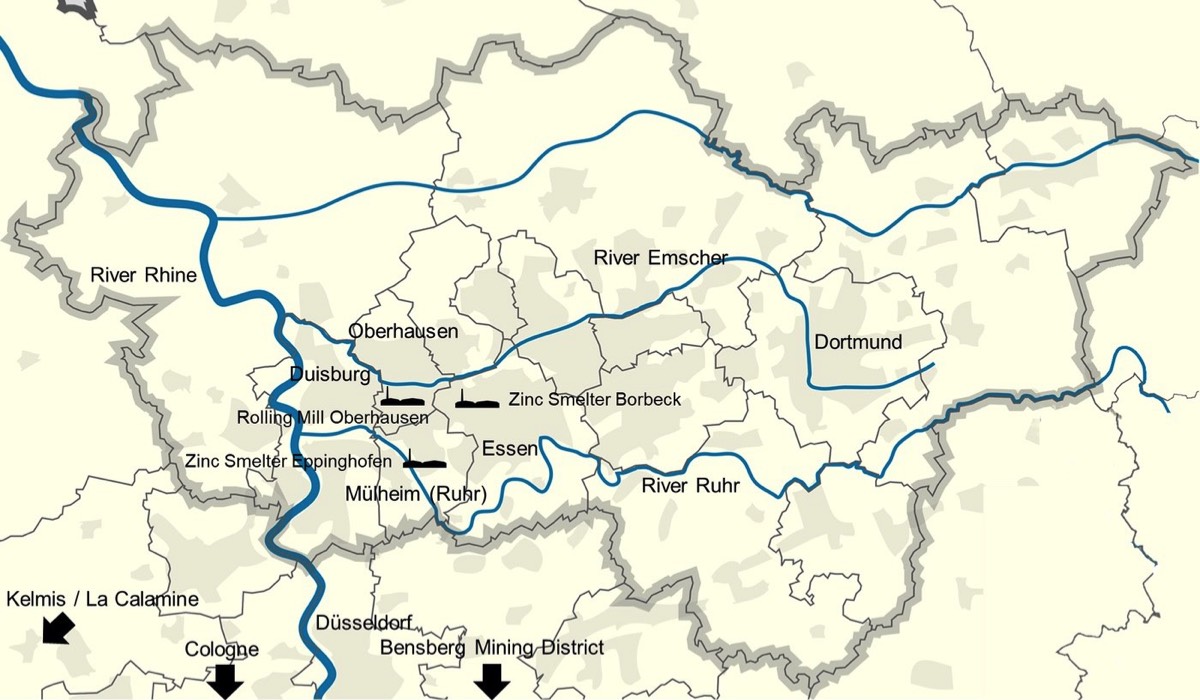

Germany was the first foreign country the VM expanded to. The VM realized the importance of Prussia and other German states (German as a national state was founded in 1871) as a sales market shortly after its foundation. However, there were great tariff barriers that made a profitable export of zinc products from Belgium nearly impossible. To avoid these barriers, the VM first planned to take over a mill in the area of Aachen just on the other side of the border. When this failed, it took until the 1850s to start a new attempt to expand into Germany, precisely to the newly evolving industrial area at the Ruhr River and to several mining areas.

The Ruhr

The Ruhr or the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial district was the central heavy-industrial region in Germany. Beginning around 1850, a large industrial belt based on coal mining, iron and steel production as well as on chemistry evolved north to the river Ruhr. Besides heavy industry, there also were other branches such as glass, brewing, engineering or non-ferrous metals at the Ruhr. The Vieille Montage concentrated its smelting and processing activities in Germany on this region.

The Ruhr not just offered a huge supply of hard coal needed for the roasting and smelting processes. The area also promised direct access to the booming markets in the German states. The construction of the railway line from Minden to Cologne in 1845-1847 and the proximity of the river Rhine made the area accessible. This infrastructure helped to create a connection to the sources of raw materials as well as to the sales markets in urban centres like Cologne.

The history of the Ruhr area as an industrial centre lasted for about 150 years. It ended with the decline of mining and heavy industry which had begun in the 1960s. This has led to a largescale process of deindustrialization by which the region is still affected today. During this time also the VM and its subsidiaries, respectively ceased their manufacturing activities in Germany. The zinc industry underwent a similar process of structural change as other branches. The implementation of electrolysis lead to shutdowns of the smaller metallurgical zinc smelters like the VM plants in Germany.

Contents

Bensberg (Mines)

Bendisberg (Mine)

Wiesloch (Mine)

Mülheim (Smelter)

Essen-Bergeborbeck (Smelter)

Oberhausen (Rolling Mill)

AG des Altenbergs (Subsidiary)

SCHLESAG (Affiliated Company)

Mülheim

(roaster, smelter and zinc oxide plant)

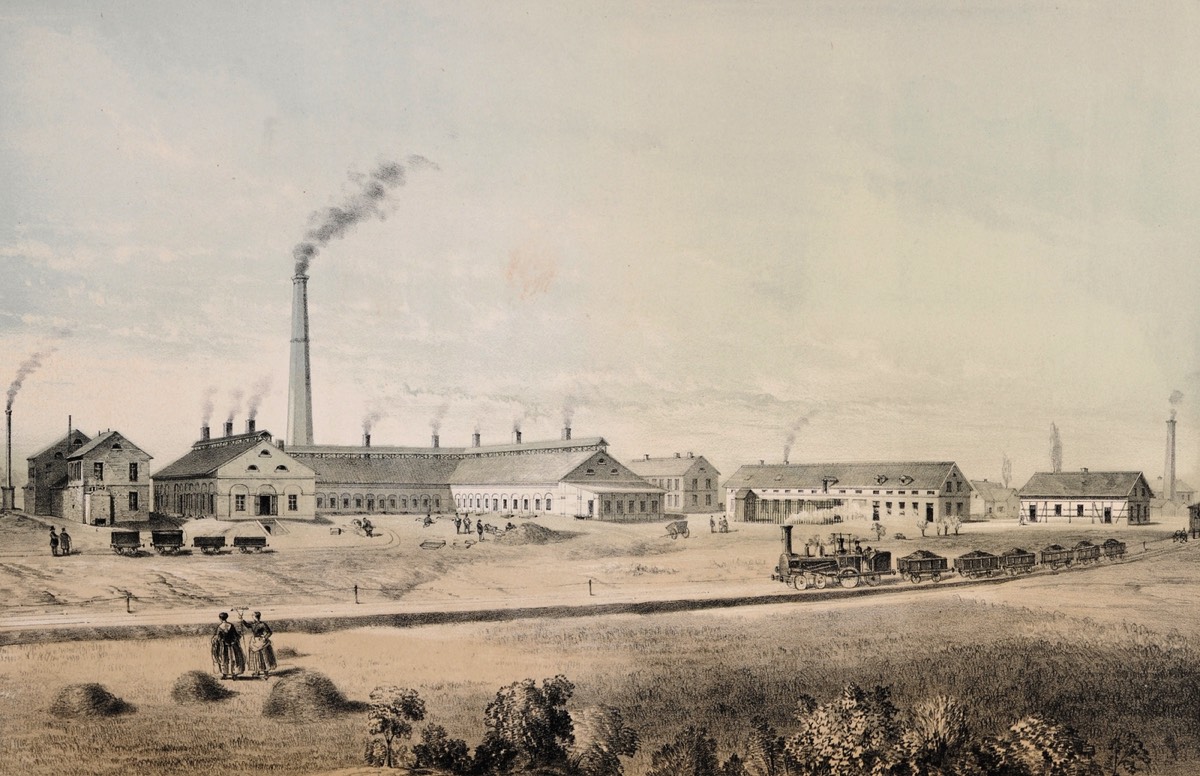

Lithography by Adrien Canelle, around 1856 LVR Industrial Museum

The zinc smelter in Mülheim-Eppinghoven was the VM’s first step into the Ruhr area. The smelter belonged to the insolvent Société Antonius which also possessed mines in the area of Bensberg. The VM created a new company named Société de la Prusse-Rhénane (Prussian Rhineland) and held 50% of the shares. However, the VM soon experienced difficulties in the administration of the different companies and decided the merge with the Société de la Prusse-Rhénane.

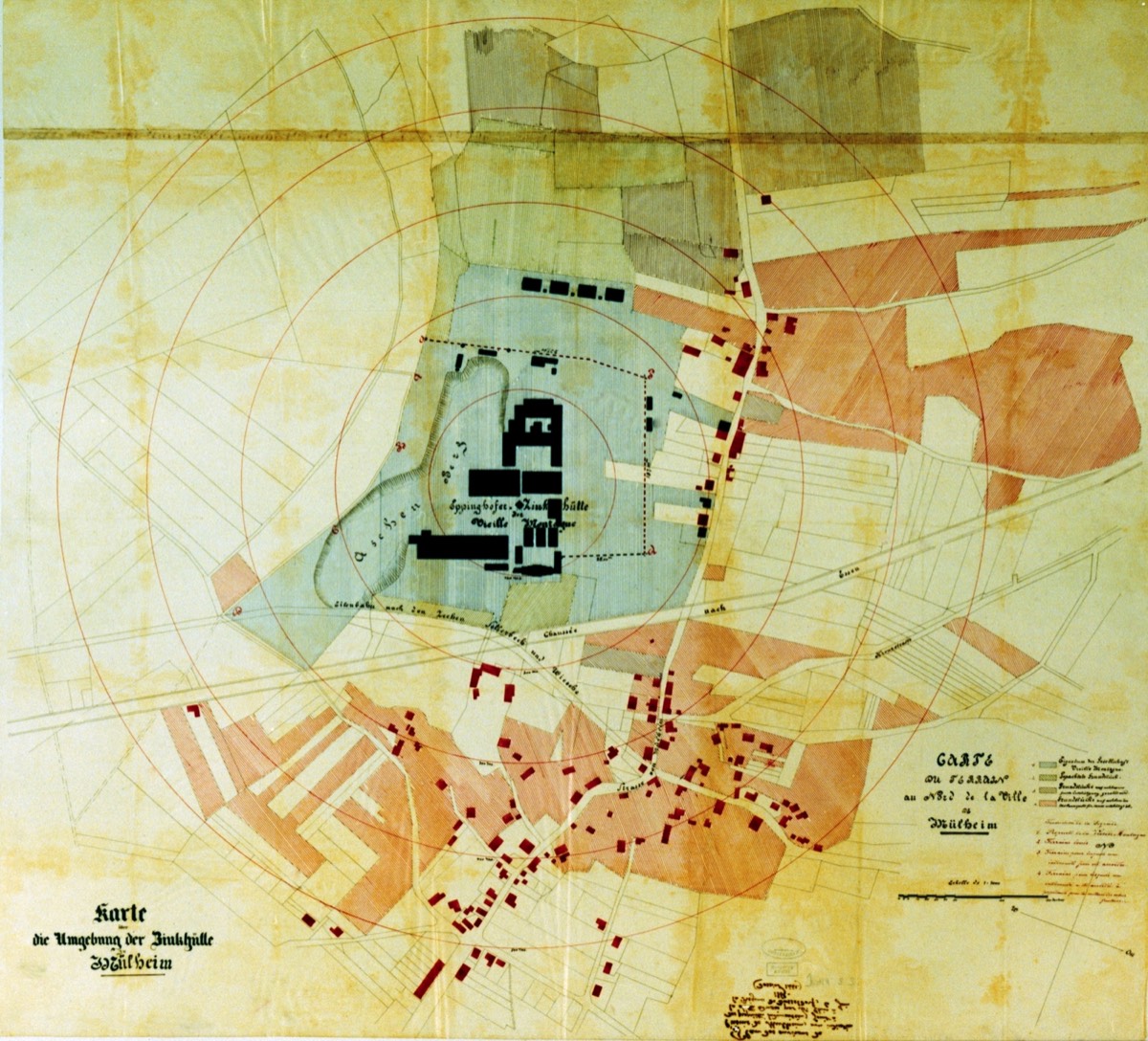

Zinc roasting and environmental consequences The zinc smelter had already been founded in 1845 but faced technical problems in production. The VM brought Belgian engineers to its new factory to get the production running. But even after that, the smelter was far from working undisturbed. There were constant disputes on environmental issues. The cause of these quarrels was mainly the roasting plant. The ore the VM used was sphalerite or zinc sulphite. As the ore contained sulphur, it had to be roasted at first to remove the sulphur. This means the ore was mixed with coal and “burned” in a furnace. These roasting furnaces produced zinc oxide and exhausted sulphuric gases.

Farmers from the neighbourhood constantly complained about the pollution that severely affected the fields and gardens. Disputes over pollution by industrial facilities – especially the highly toxic exhaust gases and wastes from zinc smelters – were nothing unusual. However, here it was an exceptional situation. There were big landowners among the complainants. Finally, the VM got tired of the constant trials and payment of compensations. The smelter was given up in 1873 after a fire. The remains of the buildings and equipment were sold.

Map showing the influence of the exhausts of the zinc smelter on nearby farmland, about 1870

Essen-Bergeborbeck

(roaster, smelter and sulphuric acid plant)

Lithography by Adrien Canelle, around 1856 LVR Industrial Museum

The facility in Essen-Bergeborbeck (or short Borbeck) was founded in 1847 by Lecomte & Co. and later operated by the Société de Nassau. It was taken over by Société de la Prusse-Rhénane in 1852 which merged with the VM one year later. There were similar disputes about the pollution as there were in Mülheim. In the case of Borbeck, the problems were finished with the relocation of the roasting plant to Oberhausen in 1857.

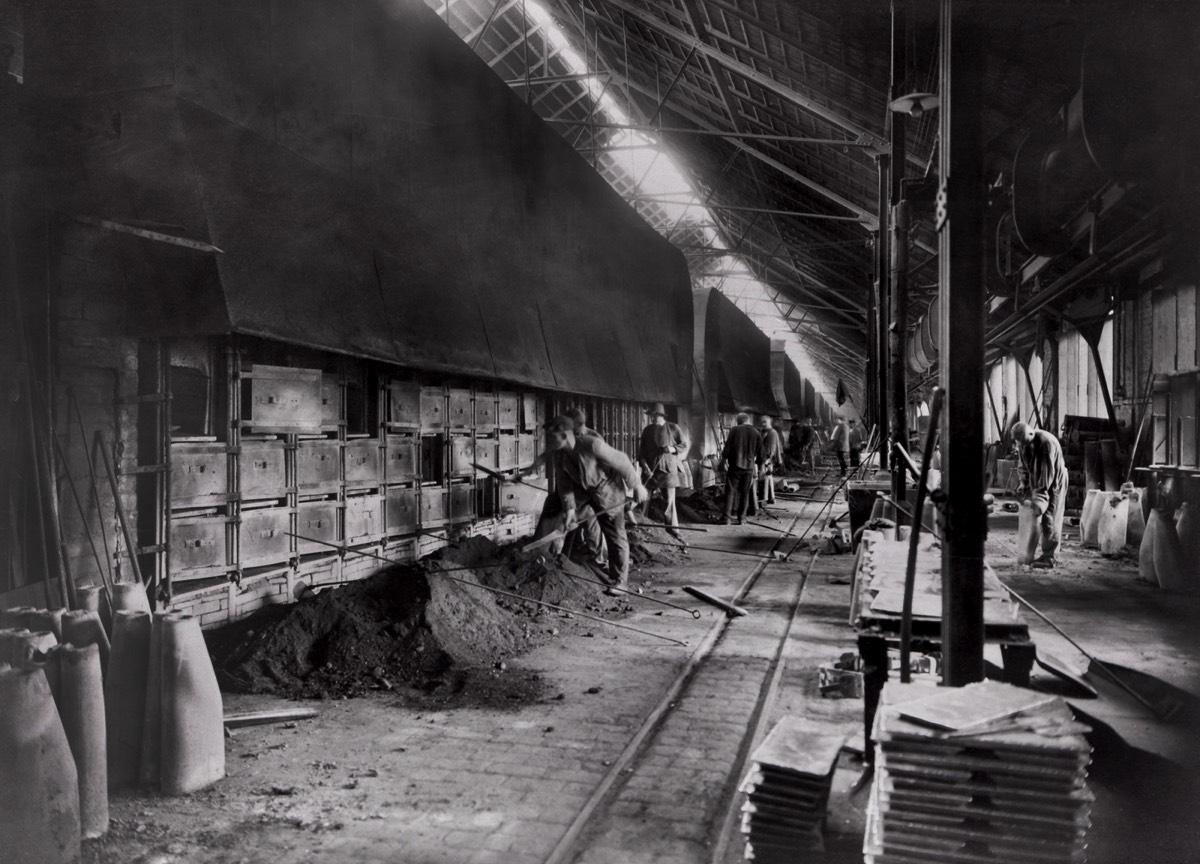

Zinc smelting process

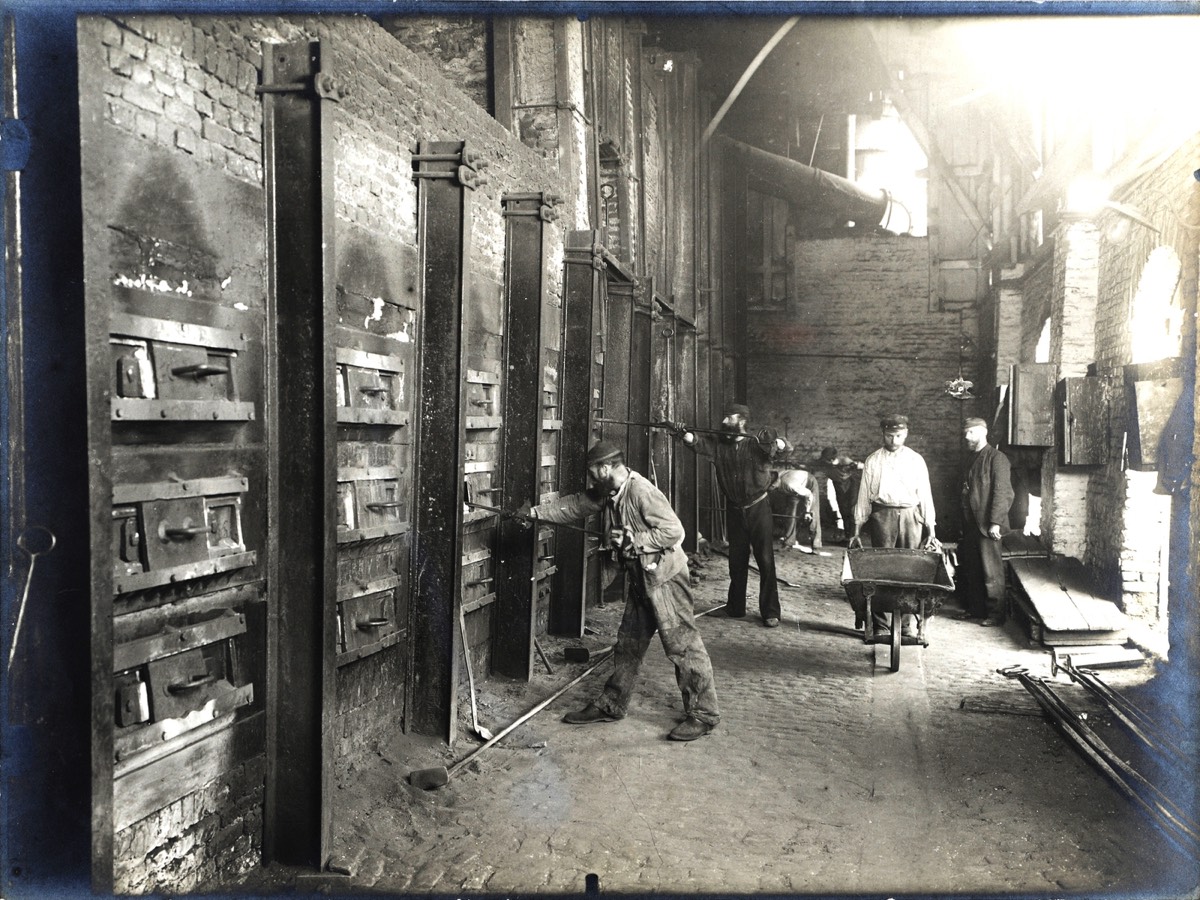

Borbeck – just like Mülheim – operated smelting or reduction furnaces besides the roasting furnaces. These ovens extracted oxygen from the zinc oxide and produced raw zinc. Therefore, the zinc oxide that came from the roaster was filled into big tubes. These tubes – called muffles or retorts – were made of clay. Zinc oxide was mixed with coal and then the mixture was heated to above 1000°C. In this way, the zinc evaporated and the carbon from the coal removed the oxygen. The raw zinc then condensed in pots attached to the muffles.

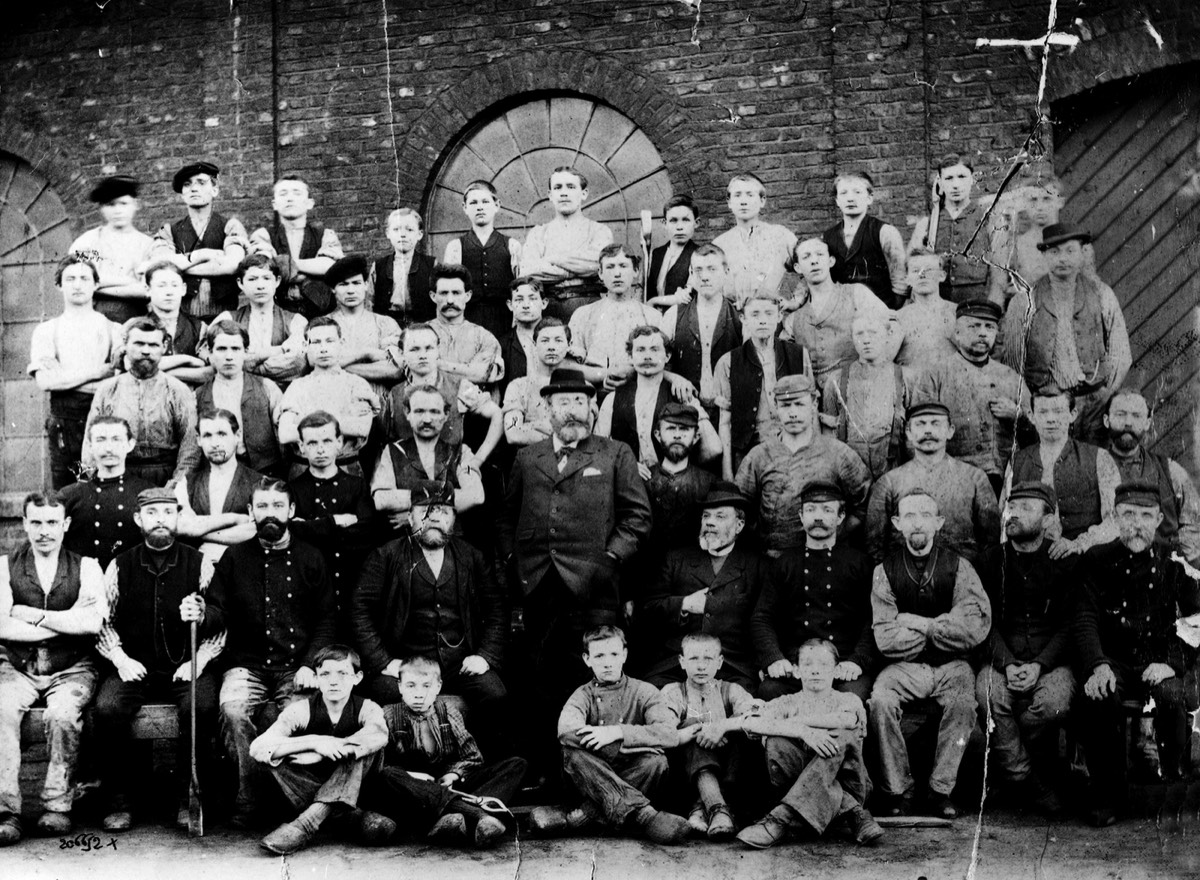

This was a very complex process and a very exhausting work. The workers had to move all the materials manually and transport the heavy muffles. Whilst that, they were exposed to immense heat from the ovens. During one shift they lost about 5 kg of body weight. They also inhaled toxic exhaust gases which contained lead, cadmium and similar substances.

Reduction furnaces during the charging with coal

The smelter in Borbeck first used so called Silesian furnaces which used much bigger pots for the smelting of zinc. Mülheim instead used Belgian or Liège furnaces which went back to the smelting technology once developed by Dony. The Silesian furnaces were developed in Upper Silesia. Borbeck switched to so called Rhenish furnaces sometime in the 1870s or 1880s. These furnaces were a combination of the Belgian and Silesian furnaces that were probably first developed by the VM in Valentin-Cocq and Viviez.

After the moving of the roasting plants from Borbeck to Oberhausen and the closing of the facility in Mülheim there was a certain division of labour: roasting in Oberhausen, smelting in Borbeck, refining and rolling in Oberhausen.

Rationalisation 1920s

In the 1920s the smelter in Borbeck was rebuilt after a major fire in 1919. That was probably part of a general trend of rationalisation of the economy. The roasting plant was relocated from Oberhausen to Borbeck. So, they eliminated additional costs for transportation. Attached to the roasting plant the VM built a sulphuric acid plant to process the exhaust gases. The rebuilding of the facility largely increased the production capacities for zinc .

Structural Change

After World War II a major structural change began which especially affected the German sites. On one hand zinc was replaced by plastic in more and more goods of every day life. On the other hand zinc companies were forced to concentrate production on few sites with high production capacities and modern technology. While the zinc smelter in Borbeck still used the old horizontal muffles, electrolysis had become state of the art. This technological backlog forced the smelter in Borbeck to abandon zinc smelting in 1968 and sulphuric acid production in 1972. The facility began to produce galvanised gratings and other building material instead. In 1981 the production was finally relocated to a site in the port of Essen on the Rhine-Herne Canal. The activities at the new site were ceased only a few years later and the VM and its successors just kept a distribution office.

Wasteland after the demolition of the zinc smelter, 1970s Photo by: Joachim Schumacher LVR Industrial Museum

Oberhausen

(1853-1981: roaster, rolling mill and processing facility)

Lithography by Adrien Canelle, around 1856 LVR Industrial Museum

The smelters in Mülheim and Borbeck lacked a possibility to process their intermediate products. For some time they commissioned the rolling mill of Friedrich Grillo in Oberhausen to roll zinc sheets. But in 1853 the Société de la Prusse-Rhénane had already purchased a real estate next to the railway station Oberhausen. That was to become the centre of Oberhausen a decade later.

In 1854 the rolling mill in Oberhausen, now owned by the VM, started production at this place. The site offered ideal conditions as there was a direct access to the railway and a coal mine next to the rolling mill. At this time Oberhausen as a city did not exist yet. The VM was thus one of the first industrial facilities built in the region. This area became the community of Oberhausen in 1862. Because of a lack of public administration in the time before, private companies took over some public duties. Thus, the private fire brigade of the company was in fact the first in Oberhausen.

Fire brigade of the VM in Oberhausen

Toxic water wells

As in Mülheim and Borbeck, the VM faced legal disputes about the pollution in Oberhausen. Pollution became apparent when the roasting plants were transferred to Oberhausen in 1857. In addition to the pollution of farmland and gardens there were complaints about the intoxication of ground waters in Oberhausen. It went so far that the city council forbid to use water wells in the city. Therefore, the VM participated in founding a company which supplied the city with water from the river Ruhr south of Oberhausen. The VM and the other companies aimed to supply themselves with clean water for industrial purposes. The ordinary people had to rely on the dirty water wells for several decades.

Roasting furnaces, 1890s

The legal disputes encouraged the VM to experiment with new roasting processes. They constructed furnaces which collected the sulphuric gases. They wanted to prevent the gases from polluting the environment but mainly wanted to use the gases for the production of sulphuric acid. Therefore, the VM cooperated with the Rhenania chemical plant right next to the rolling mill. Furthermore, Director Gustavé Ross, later director of Baelen, tried to mechanize the work at the furnace, but with few successes.

Zinc refining and rolling

Besides the roasting, the processing of the raw zinc from Borbeck was the main purpose of the facility in Oberhausen. The raw zinc was refined in Oberhausen. Hence, it was smelted in a furnace in which the different elements of the fluid metal were separated. Lead sank to the bottom as it was heavier than zinc. The zinc was taken out manually and casted.

Afterwards the fine zinc ingots had to be rolled to sheets. The workers used the so-called package rolling process. They had to move ingots into a roller. After the first rolling the sheets were lifted over the roller manually to roll them again. The workers repeated this procedure several times on different rollers until the sheets had the right strength. Later the sheets were finished on a second roller. During these processes the zinc still had a temperature of about 150 °C. That heavy work caused severe harm to bones and joints of the workers. The handling of the tools induced painful injuries of the skin. Working near the ovens additionally let the workers inhale lead and other toxic substances.

Workers’ accommodations

Many workers lived in the neighbouring workers’ colonies Gustavstraße and Familienstraße which still exist today. The VM was a pioneer of corporate welfare in the community. The VM had to offer outstanding incentives as working in the zinc industry was one of the hardest and most dangerous jobs to get.

Workers’ Colony Gustavstraße

Rebuilding of the rolling mill, 1904-1912

Most of the buildings, that still remain today, were erected between 1904 and 1912. In this time the VM rebuilt the rolling mill and started to use electricity for the rollers. They erected a boiler house and electricity plant on the compound to provide power supply. They also constructed a new roller hall, a storage building and new maintenance workshops. The most representative building is, however, the director’s manor house from 1912 which even used to have a palm house. Plans to build a lead smelter were not realised.

Warehouse of the rolling mill; rolling hall on the far right; walled garden of the director’s house on the left, 1920s (?)

Rolling hall with electrical engines, 1920s (?)

Wartime, 1939-1945

During World War II zinc manufacturing was considered to be a crucial industry. Sulphuric acid was needed for explosives and zinc was needed to produce brass for ammunition or to replace aluminium. As in other industries, the rolling mill in Oberhausen, now called Altenberg, used forced labourers, mainly prisoners of war or civilians from the Soviet Union. Due to the air raids the production in Oberhausen was ceased in 1944. After the war the sites were marked as “Belgian property” to prevent allied troops from dismantling the factories.

Structural Changes

The next great upheavals occurred as the structural change of the zinc industry affected the rolling mill in Oberhausen. The management wanted to meet the decreasing demand by starting to manufacture new products. A subsidiary company named Kräussl for instance developed a process to coat zinc sheets for offset printing. Furthermore, the Altenberg company started to produce special zinc alloys for different purposes from the automotive industry to model trains. The processing capacities were also enlarged by the construction of a new workshop for roofing materials.

Workshop for roofing material, 1970s LVR Industrial Museum

Dispite of these attempts, most of the production technology remained outdated. Most rollers still had to be operated by hand and just few steps were automatised. In this situation the city council of Oberhausen made a plan for the further development of the area surrounding the rolling mill. The Concordia colliery neighbouring the rolling mill had been shut down in 1968. The area of the mine was turned into a residential area with a shopping mall. And the city wanted to add the property of the zinc rolling mill to this new quarter.

From zinc to culture

The city and the management of the two Altenberg zinc works agreed on relocating the facilities from Oberhausen and Borbeck to a new site at in the port of Essen after long negotiations. The expectations of the increase of population in Oberhausen proved unrealistic. So, a new discussion about the future of the rolling mill began because no more residential buildings were needed.

A citizen movement formed to occupy the compound and started to use the buildings for different cultural purposes. The whole project was at stake when the enormous pollution of the area became obvious. Finally, the area was cleaned up and the intoxicated soil was sealed.

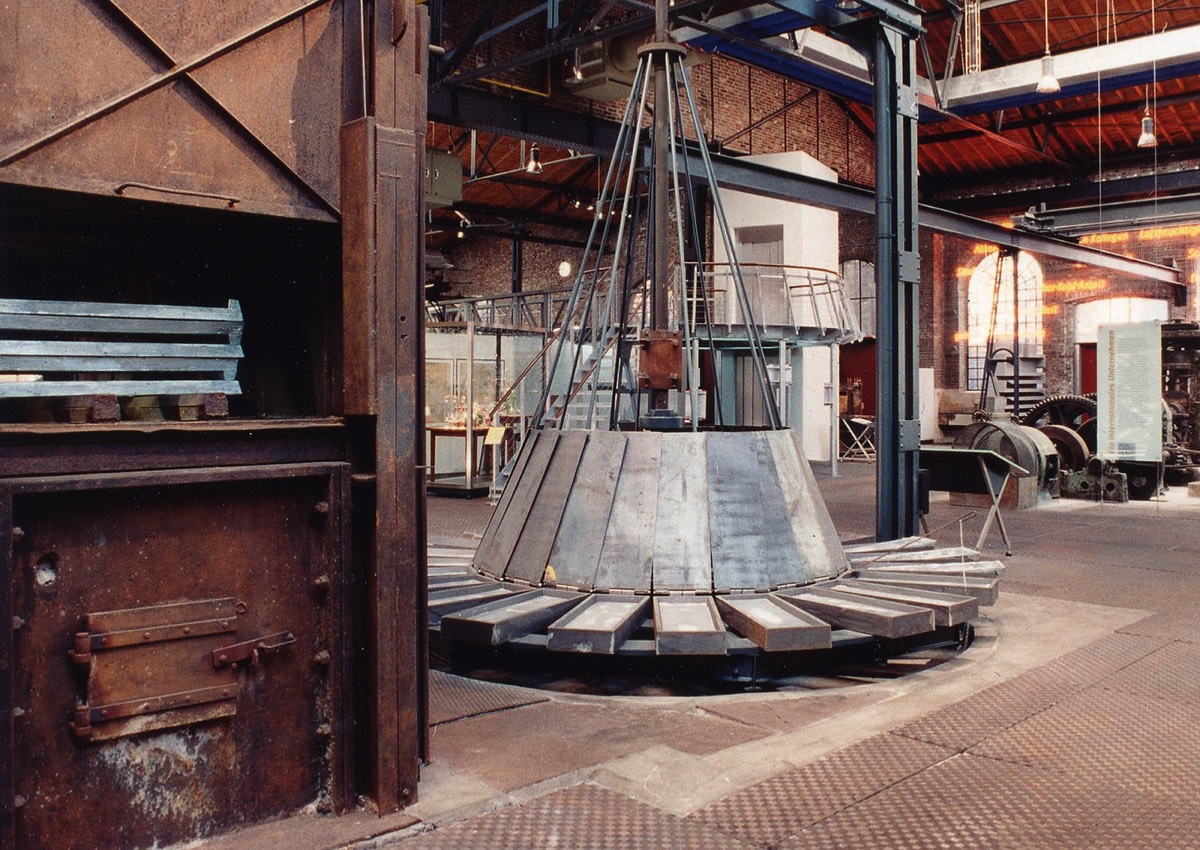

Today the former rolling mill is home of the Industrial Museum Altenberg Zinc Works, belonging to the regional authority of the Rhineland (LVR), the History Workshop Oberhausen and the association of the Socio-Cultural Clubs of Altenberg which runs a discotheque, a cinema and an art gallery.

Former refining furnace as part of the exhibition of the Industrial Museum, 1990s LVR Industrial Museum

Discotheque in one of the former maintenance workshops © Zentrum Altenberg, Oberhausen

AG des Altenbergs

(Subsidiary) In 1934 the VM formed a subsidiary company named “AG des Altenbergs”. The company consisted of the smelter in Borbeck, the rolling mill in Oberhausen and all mining sites in Germany. Altenberg is the German translation of Vieille Montagne resp. the German name of the Vieille Montagne mine in La Calamine. The VM used the German expression Altenberg all the time together with the name Vieille Montagne. With the foundation of the subsidiary the administration of the VM gave up direct control over their facilities for the first time. The reason was the political situation in Germany of course. The Nazi regime was discontent with having an important industry in control of a foreign corporation. On the other hand, the VM may have wanted to gain profit from financial support for the industry by the Nazi government. During World War II the AG des Altenbergs formed a syndicate with the Stolberger Zink AG, the second big manufacturer of zinc in Germany. From the end of the War until the closure of the manufacturing sites the AG des Altenbergs remained an independent subsidiary.

SCHLESAG

(Affiliated company) The Schlesische Aktiengesellschaft für Bergbau und Zinkhüttenbetrieb (Silesian zinc mining and smelting stock company, short: SCHLESAG) was founded in 1853 in the region of Upper Silesia. The area is now part of Poland but used to be a part of Germany until the end of World War I. Upper Silesia was the second important mining and industrial district in Germany beside the Ruhr. Because of rich coal and ore deposits it became an industrial area in the first half of the 19th century. For instance, the first coke blast furnace in Germany was operated in a state-run ironwork in Silesia. And Silesia also became a centre of zinc production. The Silesian zinc industry in fact became a serious rival to the VM. One motivation for the expansion to Germany was the wish to force Silesian manufacturers to negotiate on a cartel. But the VM went further. Together with German traders and bankers Count Guido Henckel von Donnersmarck founded the SCHLESAG in 1853. Henckel von Donnersmarck was a noble landowner and proprietor of calamine deposits. He also had personal ties to France. So the VM was an obvious partner. Leading members of the VM joined the supervisory and the administrative boards of the SCHLESAG. However, just after about four years the VM lost interest in the SCHLESAG and seems to have withdrawn from the company.